| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

World War II began in Europe on September 1,1939, with Germany's invasion of Poland. Nazi policy against the Jews, limited to the isolation and forced immigration of German Jews, now took a new and furious turn. On July 31, 1941, Marshal Hermann Goering authorized SS Gruppenfuehrer and Chief of the German Security Forces, Reinhard Heydrich, to finalize preparations for the exterminations: "...I hereby commission you to carry out all necessary preparation with regard to organizational, substantiative and financial viewpoints for a total solution of the Jewish question in the German sphere of influence in Europe. Insofar as the competencies of other central organizations are hereby affected, these are to be involved." January 20, 1942, SS Gruppenfuehrer Reinhard Heydrich called a meeting to confirm his plan to key officials. This meeting is now known as the "Wannsee Conference", named for the Berlin suburb where it was held. The only purpose of this meeting was to organize and coordinate various governmental agencies to carry out the "Final Solution to the Jewish Problem". The Conference made genocide a fact for the rest of occupied Europe. Soon that same year, under a secret code name "Operation Reinhard" three death camps were build in rapid succession: Belzec completed in March, Sobibor built in April, Treblinka in July. Under the supervision of SS General Odillo Globocnik and staffed by personnel from the euthanasia program in Germany (killing of deformed, mentally retarded Germans in gassing installations) discontinued in Germany due to the outcry of the church, these camps began a vast extermination program which did not end until Polish Jewry had virtually ceased to exist. In each one of these camps hundreds of thousands of Jews were killed. Despite this, these names except Treblinka where most of Warsaw Jews were killed, are not as well known as those of other camps like Auschwitz or Dachau, despite the fact that in the "Operation Reinhard" camps more Jews were killed than in Auschwitz. The reason is simple. They were top-secret installations and in the few recovered documents were referred to as "Durchgangslagers" (transit camps). They were dismantled and all signs of their existence were removed long before the Allies arrived.

Martin Borman's Letter Relaying the order from Adolf Hitler barring public reference to the Final Solution.

English translation of Martin Borman's Letter Relaying the order from Adolf Hitler barring public reference to the Final Solution.

Deporation of Jews to Sobibor.

Detail map of occupied Poland.

Location of the "Operation Reinhard" installations in occupied Poland.

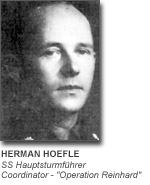

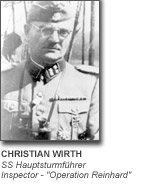

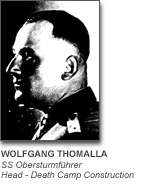

Chain of command - Operation Reinhard, 1942-1943. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

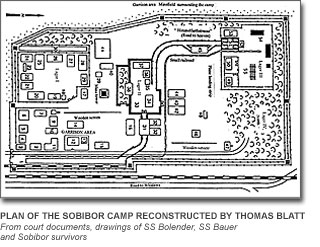

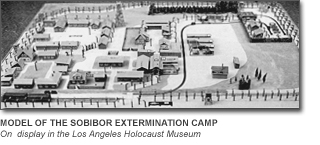

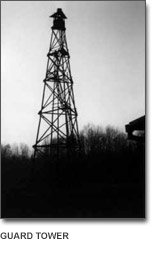

The Sobibor camp was located three miles from the Bug River in a sparsely populated area in the eastern part of occupied Poland, near the village of Sobibor, between the cities of Chelm and Wlodawa. The initial 30 acres of camp territory was later expanded to 145 acres. Camp security was crucial to the death camp. At Sobibor it included an excellent lighting system in and around the camp which had an independent electric aggregate, multiple barbed wire fences intertwined with young pine branches to conceal the interior. Besides the main observation tower in the middle of the camp, a series of smaller guard towers surrounded Sobibor. Added to the security was a 15 meter-wide minefield around the perimeter. The interior of the camp was divided into five main sections: "Vorlager" or garrison area and four inner sections called Lagers: II, III, IV and I. Separately partitioned with barbed wire fence these were, in essence, cages within cages. A brief description reveals both their relationship to one another and their separate functions.

The GARRISON AREA included the main entrance gates, the extension rail from the main outside depot and the railway platform where the victims were taken off the trains. The Commander's villa "Swallows' Nest" stood opposite the platform and was flanked on the right by the guardhouse and on the left by the armory. The SS villa known as "The Happy Flea", as well as additional SS quarters, garage, mess hall and other buildings were built nearby. The barracks of the Ukrainian guards' were located just to the north, opposite the fence. LAGER I was built directly west and behind the garrison area. It was made escape proof by extra barbed wire fences and a deep trench filled with water. The only opening was a gate leading into the garrison area. This Lager was the living barracks for Jewish prisoners and included a prisoner's kitchen. Each prisoner was given approximately twelve square feet of sleeping space. The women prisoners slept in a separate barrack. Jews employed in Lager I provided services for the Nazi staff: tailors and shoemakers, shops for carpentry, mechanical and other maintenance needs. After work, the Jewish prisoners from throughout the camp (except Lager III) were assembled in Lager I for roll call and night lock-ups.

LAGER II was a larger section and included a variety of essential "services" for both the killing process and the everyday operation of the camp. Worked by 400 prisoners, including women, Lager II contained the warehouses used for storing the articles taken from the dead victims, including hair, clothes, food, gold and all other valuables. This Lager also housed the main administration office. It was at Lager II that the Jews were "greeted" and prepared for their death. Here they undressed, women's hair was shorn, clothing searched and sorted and documents destroyed in the nearby incinerator. The victim's final steps were taken on a sandy pathway 164 yards long and about 10 feet wide framed by barbwire. Cynically called "Himmelfahrtstrasse" (Heavenly Way), it led directly to the gas chambers. LAGER III was where the victims met their end. Located in the northwestern part of the camp, there were only two ways to enter the camp from Lager II. The camp staff and personnel entered through a small nondescript gate. The entrance for the victims was also the place of their earthly exit; it descended immediately into the gas chambers decorated with flowers and a Star of David. The structures there included (besides the gas chamber and the open-air crematorium) a special cage like enclosure for the 150 Jewish prisoners working there. The camp was constantly rebuilt and expanded. The chambers, no longer large enough to handle the large waves of victims, were demolished in August, 1942 and a new massive building with about twice the number of gassing units was built. A long corridor two yards wide led to the gas chambers with the inscription "Bathhouse". These new gas chambers were 4.40 yards by 4.40 yards and 2.42 yards high. The victims entered the gas chambers trough small doors; they exited through large swinging doors that led to 32 inch-high ramps, making it easier to unload their bodies. Tightly packed, one chamber held 450-500 people. The engine that generated the deadly carbon monoxide was in a small shed adjacent to the gas chambers. The Nazi staff was sent from the discontinued (due to the outcry of the church) Euthanasia program in Germany. It included the first commander of Sobibor, SS-Hauptsturmfuehrer Franz Stangl, who later in August,1942 was replaced with SS-Hauptsturmfuehrer Franz Reichleitner and a group of 30 non-commissioned officers of which about half was always rotating on special leave. A force of about 120 Ukrainians were always on guard duty. The Jewish prisoners accounted for a total of close to 650 men, including about 100 women and 150 prisoners separated in Lager III.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

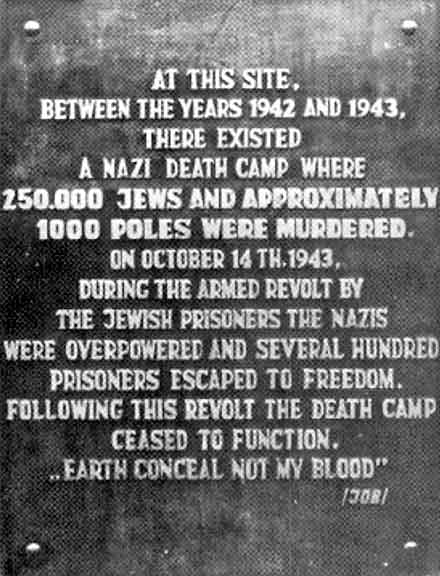

The SS contracted the "fare" for transporting the Jews to their death with the German railroad authorities: children up to 10 years of age traveled half the regular fare and those under 4 years old traveled free with their parents. The SS paid for their transportation from the funds robed from their victims. From the end of July to the beginning of October,1942 the railroad was on repair and alternative forms of transports were found: trucks, horse drawn wagons, even forcing the Jews from local villages and towns to came by foot. Later the railroad transport resumed bringing Jews from Holland, France, the Soviet Union and other countries. In the Hagen court proceedings against former Sobibor Nazis, Professor Wolfgang Scheffler, who served as an expert, estimated the total figure of murdered Jews at a minimum of 250,000.

Sketches by Josef Rychter (on scraps of newspapers) Only his name is known. He risked his life to record the Nazi crimes around Sobibor.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The proceedings of the extermination followed two scripts: for Polish Jews already aware of Sobibor's true function, their treatment from arrival to their death in the gas chambers was cruel, accompanied by shots, killing on the spot for the slightest resistance, beating and terror. The foreign Jews not aware of their fate were threatened with deceptive care, even politeness, until the doors of the gas chamber. The following description of the fate of a typical Dutch transport of 2,500 Jews will help you understand how millions could be killed so easily. Excerpts from Thomas Blatt's diary describe the arrival of a Dutch transport: "...The arriving passenger train stopped outside the camp at the small, obscure station amidst a wild forest. Inside, every available seat was taken. Soon eight to ten cars were detached from the rest and pushed onto a sidetrack leading into the camp. The Germans and the Ukrainian guards were posted around the platform and waiting (1). At the Nazis' signal, people were ordered to alight. After leaving the heavy luggage behind on the train platform, a column of about 500 people started towards a long barrack (31) with large gates on opposite ends. Attached to the right side of the barrack were smaller barracks (32). When they entered they were ordered to leave any handbags they still carried. The moment the barrack was empty, prisoners called "pakettentragers" (package carriers) opened doors to the adjoining barracks (32), and quickly transferred all the handbags to be sorted. The purses were emptied onto tables and the contents were thrown in the proper containers: money with money, brushes with brushes, lipsticks with lipsticks, etc. Finally, documents, pictures and other papers were taken in blankets to the incinerator. While this was happening, the victims were led to a yard with an overhanging roof (33). There SS Scharfuehrer Herman Mitchell in a quiet, convincing voice, welcomed the Jews. He sympathetically apologized for the inconvenience of the trip and the difficulty in extending them a roof and a bed to relax in right away. First he explained, because of strict sanitary conditions, they must shower and be disinfected. Later, he assured them the able-bodied would work, get paid and live with their families until the war was won. The soothing speech of the well-mannered SS man had its effect.

The women and children brought in first, undressed and proceeded through the narrow alley between barbed wire fencing towards three connected barracks 100 meters away (45 ). There a group of prisoners, ironically called "friseurs" (barbers) by the Nazis, were waiting to cut their hair. It was done quickly with a few nervous clips of the scissors. The young girls, visibly ashamed, sometimes begged the "barbers" not to cut too short. They were certain a shower would follow. A German stood in the middle of the room with a whip in his hand, supervising and making sure the "barbers" would not speak to the victims. It was not necessary. The poor victims would not have believed them anyway. Now robbed of all their possessions, even their hair, the Nazis prepared to take their lives. The gas chambers were only four yards away. And soon they walked innocently to its open gates to be brutally packed into the gassing units (51). SS Bauer and a Ukrainian named Emil started the engine (52) and soon a horrifying mass scream could be heard. At first it was very loud and spontaneous. About five minutes later it gradually subsided until finally a contrasting silence took over. The next ten cars of people, by this time, were on route to the yard for the speech and surely heard the cries. But mixed with the roar of the engine and muffled by the thick walls of the gas chamber, it sounded from distance like thunder. Only the prisoners, their hearts frozen in terror, knew the truth. Before piling the bodies on the pyres (55), the gold teeth were pulled by the "dentist" and other body cavities were searched for more possessions, all with restless speed. Now, the victims dead, the prisoners finished sorting out the clothing. First, they removed the Star of David and checked every fold for hidden valuables. Then they packed them in lots of ten tying with string and stored them in huge warehouses (44) to be sent later. Simultaneously, the hills of private documents, diplomas, pictures, etc. were being burned in a specially built incinerator (46), removing the last traces of their existence. Thus, the destruction of a transport of Jews was completed. The people killed, the goods stored, the documents destroyed... as if, IT NEVER WAS."

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

On April 28, 1943 a transport of Polish Jews from the town of Izbica arrived at Sobibor. Because of Sobibor's planned expansion the Nazis selected 40 Jews to work in the camp. Those Jews brought to the hermetically isolated prisoners of Sobibor the stunning news about the Warsaw ghetto uprising. It was the spark to fight back. A nucleus of a conspiracy was established. Its leader was Leon Feldhendler, a thirty-three year old. A tall man, about thirty-five years old, still wearing his Red Army lieutenant's uniform attracted Feldhendler's attention. His name was Alexander (Sasha) Aronowich Pechersky, who as a former military man, emerged as the factual leader. On October l0, a consolidated command was formed. The number of the conspirators involved was kept to an absolute necessary minimum. From a total of about 550 Jews alive at the time, less that 10% had any knowledge of the escape plan. The escape was divided into three phases: Phase I - prepare the assault teams [3:30-4:00 P.M.] Phase II - eliminate the Nazis noiselessly [4:00-5:00 P.M.] Phase III - mobilization of all prisoners for an open revolt and mass escape [5:30 P.M] In the first phase, members of the Underground who had access to the warehouses and sorting sheds were told to remove and to deliver knives and small axes to the conspirators command post. Next was the placement of six combat groups, of three people each, in preparation for the secret killing of the Nazis. In the second phase, the Germans were to be trapped and executed in selected places. In Lager I mainly in the workshops. The killings in Lager II were to take place in the warehouses and in the incinerator building. The Nazis should be lured to those place under various pretexts. Put in the broadest terms, the plan called for killing as many Germans and Ukrainians as possible within one hour, and then ignite a total revolt by the rest of the by now uninformed prisoners. In its details the plan utilized the Germans' brashness and their confidence that they had total control over the seemingly subdued prisoner population. It also depended upon the predictability of their daily routine. Most important, we utilized their greed. A special group of prisoners was designated to attack the armory. All of them would be armed with knives and axes prepared to fit inconspicuously under belts when covered with jackets. A few youthful prisoners were given responsibilities as message carriers, luring the Nazis to the traps and to steal weapons. Because of their functions in the camp, their movement was not strictly scrutinized by the Nazis. They had access to places that were strategically important to the Underground, including the Nazi quarters, canteen and the incinerator. All preliminary preparations were to be completed by 4:00 P.M. Then the telephone wires should be cut at both ends and the middle section hidden to prevent the Nazis from quickly reconnecting the line. Just before 5:00, the electrician Walter Schwarz, a German Jew, was ordered to damage the electric generator supplying power to the camp. Then the elimination of the SS Staff should begin. All the Germans within reach would be quietly killed. So as not to betray the action, no one was to use (at this phase) the weapons acquired from the death enemy. Above all, everything had to have the appearance of routine. Even the behavior of the Kapos in the conspiracy was not to change and Leon urged them to make use of the whips as usual, until all workers were returned to their quarters in Lager I. If everything went well to that point, Kapo Pozycki would blow a whistle for the regular roll-call a little earlier than usual. The Jews would form a column, but instead of waiting for the Germans, they would be led by the Kapos in regular formation toward the main gate. The idea was that the guards would think it was a German order for some work assignment; this would allow the prisoners to come as close as possible to the main gate without arousing suspicion. Then the gate would be taken by storm and the guards overpowered. To the organizers' dismay, there was no way of contacting the Jews in Lager III. The escape date was originally set for October l3. Later, due to unforeseen circumstances, it was moved to the next day October 14. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

October 14, 1943 was a warm, sunny day and nothing disrupted the routine. Only a very small group knew that this was to be the fateful day. The Nazis in the camp went about their business as usual. At precisely 4:00 P.M., the stage was set. Everything now depended on the nerves of the attackers, their faith in themselves and luck. Acting commander SS Untersturmfuehrer Niemann rode up on his horse and entered the tailor shop. Mundek was ready, holding the new uniform. The German without suspicion, unhooked his belt with its pistol in the holster and causally threw it on the table. As tailors have done for ages, he patted and turned Niemann at his will. Finally he told him to stand still while he marked the alterations with a crayon. Then the blow fell. The Nazi dropped like a fallen tree, his head split. Shubayev rushed to Sasha's quarters and delivered the first pistol. They embraced. Now, there was no turning back. At 4:l5, Oberscharfuehrer Graetschus, the German in charge of the Ukrainian guards, arrived at the cobblers' shop to pick up his order. While Yitzhak held the Nazi's leg in a firm grip, pretending to pull the boots, Arcady Wajspaper and Siemion Rosenfeld slipped out from the back room and split the skull of the Nazi with the ax. Then his deputy, the Ukrainian Klatt, entered, calling his boss to the telephone. He too was attacked and killed.

In Lager II, Toivi (Thomas Blatt) standing at attention was informing a SS Untersturmfuehrer that a new leather coat, exactly his size had been set aside for him in the warehouse. The German took the bait and went without hesitation in the direction of the warehouse. Meanwhile, in one of the many partitions of the warehouse, a few conspirators were stocking packets against the wall, each containing ten articles of clothing. At the side lay the bait: a shiny, black leather coat. Wolf entered. "Attention!", barked Bunio. The prisoners froze. "Help the Herr Unterscharfuehrer with the coat!", ordered the Kapo. An inmate fetched the coat and held it for the German. The Nazi put his arm into the sleeves and in a split second the scenario changed. Held as if in a straight jacket, he could not move his arms. A strike of the ax by Cybulski and he fell. The executions in Lager II had begun: the trap was waiting for the next Nazi. The conspirators went out to summon other Nazis and when the miners' carts with food rations were en route to Lager III, SS Unterscharfuehrer Valaster, the driver, was flagged down and told that Wolf urgently needed him. He left to be killed. Another team readied for a new attack on SS Oberscharfuehrer Beckman. The prisoner Pozycki knocked at his office door asking permission to enter for some job clarification. Permission granted, they entered. Immediately, Pozycki immobilized him by a headlock and he was knifed to death. In the adjoining room, SS Scharfuehrer Valaster's body was lying on the floor. Unexpectedly, SS Unterscharfuehrer Walter Ryba had wandered into the car garage in the garrison area where he was killed. From the main tower in the center of Lager II came the sound of a bugle announcing the end of the day's work. As groups returned to the main square in Lager I, the marching songs in Yiddish, German, Polish, Dutch, Ukrainian and Russian echoed far beyond the barbed wires of the Sobibor forest. Everything appeared like any other day. In Lager I, a mass of prisoners unaware of what was about to happen stood in line for their "coffee" and bread as they did every day. Their life or death would be determined in a matter of minutes. At that moment, SS Frederick Gaulich entered the area. The prisoner Leitman immediately asked him to come to the newly built barrack because of some problem with the bunks. The moment Gaulich entered the barrack his fate was sealed; he was killed with an ax. The first dead German was discovered. Returning from Chelm, SS Bauer, drove to the garment warehouse with two prisoners, Jakob Biskubicz and David. While unloading cases of vodka from the truck, one guard looked into the office and noticed a dead German. Jakob Biskubicz describes how this discovery initiated the third phase of the revolt: "A Ukrainian came running and called to Bauer, 'A German is dead!' Bauer did not immediately understand what he meant. But David also who heard him, started to run in the direction of Lager I. Bauer ran after him and shot at him twice. I remained alone." Sasha, heard the gunfire and understood that something bad had happened. On Sasha's orders, Pozycki blew his whistle for roll call. Although it was fifteen minutes early, the Kapo's authority was never disputed and the prisoners began to gather. Now the news spread like a wildfire. Some Jews were returning to their barracks where they pulled out their white prayer shawls from their hiding places and came out assembling near the kitchen reciting "Kaddish"; the prayer for the dead, for themselves. Sasha, jumping up on a table, made a short speech in Russian, his native language. His voice was clear and loud so that everybody could hear, but also composed and slow. He told the prisoners that most of the Germans in the camp had been killed. There was no turning back. A terrible war was ravaging the world and each prisoner was part of that struggle. He promised that dead or alive, they would be avenged and so would the tragedy of all humanity. He repeated twice that those prisoners who, by some miracle survive, should forever be a witness to this crime. He ended with a call: "Forward Comrades! Death for the fascist!!!" The prisoners from various countries, speaking diverse languages, understood. From the midst of the assembled Jews a single, strange and impatient voice was heard: "FORWARD! HURRAH! HURRAH!" In a flash, the entire camp burst with the defiant call. Thomas Blatt recounted: "The remaining Germans: Bauer, Richter, Frenzel, Wendland and some guards with machine guns, who had initially been in shock, now effectively blocked the main gate. People were killed and the front line Jews mostly unarmed fell back, then a new wave of determined fighters pushed again forward towards in a suicidal thrust. Someone was trying to cut an opening in the fence with a shovel. Within minutes, more Jews arrived. Not waiting in line to go through the opening under the hail of fire, they climbed the fence. Though we had planned to touch the mines off with bricks and wood, we did not do it. We couldn't wait; we preferred sudden death to a moment more in that hell. Corpses were everywhere. The noise of rifles, exploding mines, grenades and the chatter of machine guns assaulted the ears. The Nazis shot from a distance while in our hands were only primitive knives and hatchets. We ran through the exploded mine field holes, jumped over a single wire marking the end of the mine fields and we were outside the camp. Now to make it to the woods ahead of us. It was so close. I fell several times, each time thinking I was hit. And each time I got up and ran further...100 yards...50 yards... 20 more yards...and the forest at last. Behind us, blood and ashes. In the grayness of the approaching evening, the towers' machine guns shot their last victims." |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

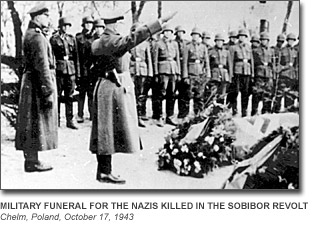

A quietness lay over Sobibor. The few Germans still alive, Erich Bauer, Karl Frenzel, Willy Wendland, Rechwald and Siegfried Wolf assessed the situation. The guards assembled, but many of their comrades were now gone. On those parts of the fences that remained standing and on the ground now torn by the explosions, bodies were lying scattered about. Taken by surprise, the Germans were unable to comprehend the situation. Was this revolt accomplished by the wretched Jews alone or was it a planned military action with the help of outside partisans? They were in a panic. The camp telephone was not functioning and Frenzel called the nearby base of the Border Police and the SS Mounted Unit in Chelm from the village train station. He also sent a chaotic message to the Security Police headquarters in Lublin asking for immediate reinforcement to save the lives of the remaining Nazis: "Jews revolted ...Some escaped ...Some SS officers, noncoms, foreign guards dead. ...Some Jews still in camp. ...Send help." The Commander of SS and Police forces in Lublin, Lieutenant General Jakob Sporrenberg, immediately informed General Frederick KrŁeger in Krakow, the Commander of all SS and Police forces in occupied Poland of the Sobibor uprising and the Nazi casualties. His cable to them follows:

"October 14, 1943, at about 17:00 hours, a revolt of Jews in the SS camp Sobibor, 40 km north of Chelm. They overpowered the guards, seized the armory and after a shutout with the camp garrison, escaped in an unknown direction. Nine SS killed. One SS wounded. One SS missing. Two guards of non-German nationality shot to death. Approximately 300 Jews escaped. The remainder were shot to death or are now in the camp. Military Police and armed forces were immediately notified and took over the security of the camp at about l:00 hours (1:00AM, October 15). The area south and southwest of Sobibor is now being searched by police and armed forces." General Hilmar Moser, wasted no time in ordering Major Hans Wagner, commander of the 689 Werhmacht Security Battalion in Chelm, to quell the uprising and capture those who had escaped by every necessary measure. Help arrived quickly in the form of a small Border Patrol unit of seven men under the command of SS Untersturmfuehrer Adalbert Benda. Late that night Major Eggert of the Security Police and Captain Erich Wullbrandt, an officer in the Security Police decorated with the highest German military honors, arrived. SS Untersturmfuehrer Benda reported: "...During the mopping up of the camp itself, our men had to use arms because the prisoners resisted arrest. A great number of prisoners were shot: 159 prisoners were treated as ordered. All the men of the Einsatzkommando were equal to their task." The next order of business was the pursuit.

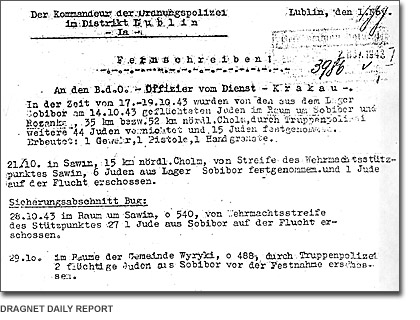

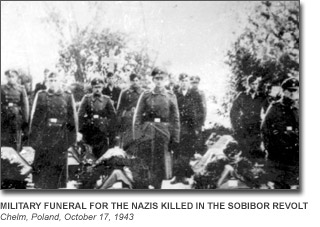

For the Jews who had escaped, the next few weeks were terrifying. They were hunted by over 100 regular soldiers, 100 mounted police and 150 Ukrainians and SS soldiers. On October 16 and 17 the second and Third Squadron of Mounted SS and Police added five hundred more men to the manhunt. This force was formidable enough; but one must add to it the auxiliary units, regional police units and local collaboration, aided by two Luftwaffe observation aircraft, to comprehend the odds against these Jews. The bridges across the Bug river were guarded and traps were set on the crossroads. Circling in the forest, some Jews inadvertently returned to the camp area where they were spotted and caught. The search was finally officially halted on October 2, but the escapees continued to be captured individually or in groups and cables were sent regularly to Krakow as each of the escapees were caught. The Security Zone Bug (Dragnet Daily Report) report pictured here reads: "In the period from October 17 - 19, 1943 Jews who escaped from Sobibor on October 14, were apprehended in the area of Sobibor and Rozanka, fifty two kilometers north of Chelm. The military police killed forty-four more Jews and fifteen Jews were taken into custody. Seized: one rifle, one pistol, one hand-grenade." "October 21, 1943 Sawin, fifteen kilometers north of Chelm, Wehrmacht posts in Sawin apprehended six Jews from Sobibor. One Jew was shot death attempting to escape." "Security zone Bug: "October 29. 43, in the municipality of Wyryki, o 489, the military police apprehended two escapees from Sobibor. They were executed.

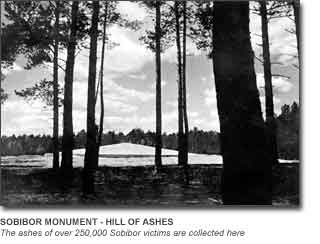

Word of the escape first got to the outside world through an October 25 cable send by the Polish underground (AK) to their government-in-exile in London: "In an heroic fight with the Germans the Jews destroyed their place of torment". This was the first and only case in which so many Nazis were killed by prisoners in a single action, in one day, during the Second World War. Bauer recalled in his post-war testimony: "...I transported seven coffins to the city of Chelm...The rest of the coffins came with the train to Chelm. Those I transported from the railroad station to the City Hall. In all, twenty-one or twenty-three persons were killed." Auschwitz Commandant Rudolf Hoes notes in his memoirs that "The Jews (of Sobibor) were able, by force, to achieve a major breakout, during which almost all the German personnel were wiped out...". The uprising in Sobibor represented one of the most heroic pages in the anti-fascist resistance in World War II, as well as in Holocaust history as a whole. It was unique in its plan and execution and in successfully eliminating most of the SS staff in the camp. As a result, the camp was closed. The area was plowed under and a Ukrainian Guard settled at the site. On another level, the Sobibor Uprising had more far reaching and tragic repercussions. On October 19, 1943 the Sobibor Revolt was discussed extensively at a meeting held in Governor General Hans Frank's mansion in Krakow. In attendance were the Chiefs of the Security Service and Police in the Generalgouvernement. Citing Sobibor as an example of danger they decided to accelerate the liquidation of the remaining Jews in camps in Lublin area. Himmler immediately ordered SS General Friedrich Krueger to carry out this policy. Twenty days after the revolt, on November 3, 1943, under the code-name Erntefest (Harvest Festival), the liquidation began. The results were staggering: 10,000 Jews were killed at Trawniki, 18,000 at Majdanek and an additional 15,000 in other camps; a total of 43,000 killed in six days. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

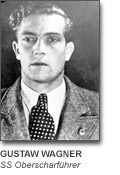

Documented proof exists that at various times, all the men listed below were at Sobibor for some length of time. Approximately 100 Germans and about 200 Ukrainian guards worked in Sobibor during its eighteen months of existence. Other than the commander and his deputy, all Germans were non-commissioned officers, but were always superior in rank to any of the Ukrainian guards. Their function in the camp varied. Some had specific assignments such as setting up the gas chambers and crematoria; other rotated from other Operation Reinhard camps. And there were some, like Frenzel, who were at Sobibor from the beginning to its end. At any given time the German personnel amounted to about 30 men, of whom approximately one half was always on rotating vacations. Having the spoils of their victims at their disposal, the Sobibor Nazis lived in the utmost comfort, supplementing military rations with foodstuffs stolen from the murdered Jews. The best tailors, cobblers, culinary experts, dentists and mechanics were kept as laborers who used their talents to make life easier for the Germans assigned to the "wilds" of Poland. Some even put in orders to the mechanics shop for bicycles made from converted baby carriages, for their children in Germany. Some enriched themselves by stealing valuables, even gold teeth pulled from the victims bodies. Safe from the front line duty, the non-commissioned officers received an average monthly pay of 58 Reichsmark and close to ten times this amount in bonuses of 18 Reichsmark a day; a total of about 600 Reichsmark. Future incentives took the form of three weeks vacation every three months. Most of these Germans, all fairly young, were family men. Some, like Frenzel, claimed even to be religious. Their job did not require them to be great managers; the barrel of a gun was persuasive enough. LEADERS OF "OPERATION REINHARD"

TECHNICIANS OF "OPERATION REINHARD"

LEADING NAZIS IN SOBIBOR

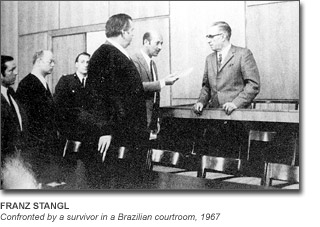

At the Nuremberg Trials, the stories of the death camps were little known. The prosecution accused criminals mostly on the basis of the atrocities at Auschwitz and other well-known Nazi camps where the evidence and witnesses were relatively easy to obtain. As for Sobibor, witnesses had dispersed and the criminals were unknown to the authorities. In May, 1945 former Sobibor staff member SS Nowak was recognized in East Germany by a former Sobibor inmate, Meir Ziss. Nowak was arrested by Soviet authorities. SS Hubert Gomerski, another Nazi from Sobibor, was also arrested. Then Johann Klier was arrested, but as a person who felt compassion for the Jews and secretly tried to help them, he was soon released.

One of the worst murderers, Erich Bauer, the chief of the gas chambers, was found fortuitously. He was recognized on the streets of Berlin by survivors. On September 1, l951 he was sentenced to death and then, after abolition of the death penalty in Germany, to life in prison. On September 6, 1965, the German court in Hagen initiated the proceedings against thirteen former Sobibor Nazis, accusing them of crimes against humanity. On December 20, l966, the following sentences were handed out:

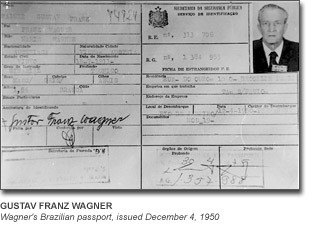

1. Frenzel, Karl, carpenter; arrested in 1962. Accused of personally killing 42 Jews and helping to murder approximately 250,000 Jews. Found guilty of personally killing 6 Jews and of helping to murder approximately 150,000 Jews. Sentenced to life in prison. 2. Bolender, Kurt, hotel porter; arrested in 1961. Accused of personally killing approximately 360 Jews and of helping to murder approximately 86,000 Jews. Committed suicide in prison before sentencing. 3. Wolf, Franz, warehouse clerk; arrested in 1964. Accused of personally killing one Jew and helping to murder 115,000 Jews. Found guilty of having assisted in the murder of at least 39,000 Jews. Sentenced to eight years in prison. 4. Ittner, Alfred, laborer; accused of helping to kill approximately 57,000 Jews. Found guilty of having assisted in the murder of approximately 68,000 Jews. Sentenced to four years in prison. 5. Dubois, Werner, mechanic; accused of helping to kill approximately 43,000 Jews. Found guilty of having assisted in the murder of at least 15,000 Jews. Sentenced to three years in prison. 6. Fuchs, Erich, truck driver; accused of helping to kill approximately 3,600 Jews. Guilty of assisting in the murder of at least 79,000 Jews. Sentenced to four years in prison. 7. Lachman, Erich, mason; accused of helping to kill approximately 150,000 Jews; freed. 8. Shutt, Hans, salesman; accused of helping to kill approximately 86,000 Jews; freed. 9. Unverhau, Heinrich, male nurse; accused of helping to kill approximately 72,000 Jews; freed. 10. Juhrs, Robert, porter and janitor; accused of helping to kill approximately 30 Jews; freed. 11. Zierke, Ernest, saw mill worker; accused of helping to kill approximately 30 Jews; freed. 12. Lambert, Erwin, tile layer; accused of helping to kill an unknown number of Jews; freed. Thus, most of the Nazis were freed in a relatively short time; their citizenship rights were revoked only for the duration of the prison sentence. The most notorious of the executioners, SS Stangl, was arrested in Brazil and extradited to Germany. On July 22, l970 the Dusseldorf Court sentenced him to life in prison for complicity in the murder of 900,000 people. He died in prison of a heart attack.

THE BEAST OF SOBIBOR

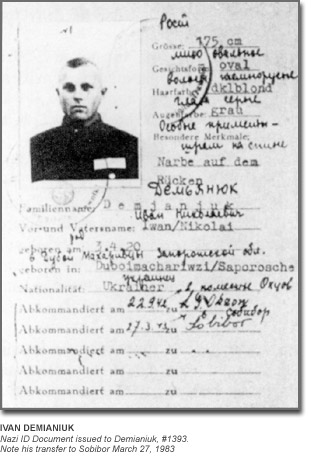

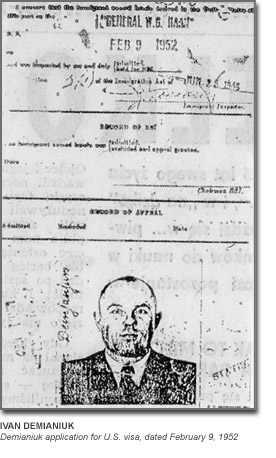

THE UKRAINIAN GUARDS The Ukrainian collaborators also went into hiding after the war. Only a few were ever caught. Some even made it to the United States and other western countries where they were received in the disguise of anti-Communists and displaced persons. One of them named Ivan Demjanjuk was a guard in Sobibor who was discovered living peacefully as a retired auto worker in the Cleveland suburb of Seven Hills. In February, 1986 he was extradited to stand trial in Israel as "Ivan the Terrible" who ran the gas chambers at Treblinka. It was never proved that Demjanjuk was indeed Ivan and the Israeli court was forced to release him. However, it duly noted that there was conclusive proof that Demjanjuk was a guard in Sobibor. Some guards were tried in the Soviet Union: B. Bielakow, M. Matwiejenko, J. Nikifor, W. Podienka, F. Tichonowski and J. Zajcew were found guilty and executed for their part in the Sobibor crimes. In April, l963 at a court in Kiev where Sasha Pechersky was the chief prosecution witness, ten former Ukrainian guards were found guilty and executed and one was sentenced to fifteen years imprisonment. In a third trial in Kiev held in June, 1965 another three former Ukrainian guards of Belzec and Sobibor were sentenced to death.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The odds were stacked against the escapees. It is estimated that about one-third of the escapees survived the liberation. The general conditions it occupied, provided formidable obstacles. The situation of a Jewish escapee stood in sharp contrast to that of a Christian escapee. The latter could simply mingle with the rest of the population and be safe. Not so the Jew. At the end of 1943, there were no Jewish communities to which the hunted could return. The Jewish hamlets and small towns, once vibrant with Jewish life, were now empty. In addition, harboring a Jew meant certain death to the person or family brave enough to do so. For the Jews, Sobibor had meant certain death; the Polish countryside or city raised the odds for survival only slightly. Stories of treachery by the indigenous population were common. Berl Freiberg tells what occurred to a large group of survivors after the escape:

"On the third day we were sitting, binding our wounds, when we saw an armed Gentile suddenly come out into the clearing... He came near us and began speaking. He questioned us and decided to take us to his group. Then he asked us if we were hungry and said he would bring back some food. He left and came back with a whole gang of armed villagers and gave us some bread. We were sitting around and eating and they asked us if we had guns, or gold. They told us to hand over our guns. That's is how it's done, they told us; later they'd return the weapons. Though we knew we shouldn't, we gave up the few light weapons we had... They started shooting at us point-blank. We were trapped! We had nothing to return fire with and it ended in tragedy. We came out of Sobibor to be gunned down by the likes of these..." Fifteen year old Berl managed to get away.

Only days after the revolt, Shlomo Szmajzner and a group of twenty one escapees were unexpectedly surrounded in the forest by supposedly friendly partisans. Shlomo's rifle was taken, they were robbed and most were murdered. During the shooting, Shlomo fell and pretended to be dead. An excerpt from his writing portrays his story: "One of the Poles who seemed to be their leader, ordered us to raise our hands for him to inspect us. What happened next was actual looting. Those who still had some gold or valuables lost everything. ...Then I realized we had fallen in the hands of hostile guerrillas. At the same time, I said to myself, ''we are done for!" The first shot came. Quick as lightning I threw myself to the ground, while the salvo was intensified. While I lay there pretending I was dead, the bandits left, since they thought their atrocious task was ended. When I realized that only silence was around me, I slowly raised my head and saw that there was no one else in sight. To my immense surprise, I noticed that both Majer and Jankel, the old tailor, had done the same. The others were all dead. ...It had to be a miracle, my being still alive, since the shots had been fired point blank. Terribly frightened, we left this sinister place immediately, now that there were only three of us. Leon and the other boys were already in Eternity. They had survived the German tyranny and not even Sobibor had finished them off. However, they had met death at the hands of their Polish countrymen..."

Even those escapees lucky enough to find shelter with the Poles often found themselves in grave danger as this entry from Thomas Blatt's diary reveals: "...One day Bojarski appeared in our hiding place, saying: "The Germans are looking for partisans in our area; they are searching in all the farms close to the woods. I'm afraid they will search mine as well and so I'm going to put you for in a more secure shelter a few days.'' Later, in the night we were led behind the barn to a patio-like roofed storage area. Close by, I noticed a two-wheel cart. In it lay a large object, round and gray. He held us each by the armpits and lowered us into the ground through a narrow hole dug in the earth. We asked for the kerosene lamp so that we could arrange ourselves in our new quarters. He gave it to us without a word and closed the opening by tightly pushing in straw. I looked around. We were in a small dugout, about four-and-a-half feet long, three feet wide and three feet high. Along the "ceiling" there was a strong pine pole and across it some smaller pine poles covered with straw and branches. On top of it must have been soil. The small, round entrance in the corner of the roof was now jam-packed with straw. While wondering where the air vent must be, we heard footsteps above, then the sound of something heavy being rolled. In a moment, an object fell with a great thud over our heads and the main pole began to crack slowly in the center to form a "V". Szmul immediately supported the pine pole with his shoulders so that the ceiling would not collapse upon us, while I tried to push the straw away from the opening in order to call the farmer. It was impossible. I began to pull out big clumps of straw, and found that something else was blocking the entry! "What's wrong?", Szmul cried out. "It's blocked! It's blocked!", I gasped. The kerosene lamp began to flicker and waver and finally went out. We could not panic, I told myself...we mustn't panic. I tried to light it again. The match lit for a few seconds and went off. "Why the hell doesn't it burn?", my mind screamed. The answer came instantly: there was not enough air. We couldn't see each other in the dark. Panicky and struggling to breathe, perspiration poured down my forehead into my eyes. It was very dark and cramped. Without oxygen we were exhausted, close to fainting and trembling with fear. Finally, with superhuman effort, Fredek managed slightly to move the heavy object blocking the entry hole, shifting it a little towards the crack of the bent ceiling. A stream of fresh air quickly revived us all, and we squeezed out. As we stood there, it flashed through my mind that there was a change in the surrounding scenery. The two-wheel cart wasn't on the side as before, but partially over our new hiding place. The handles stood high up and the body of the wagon was slanted down to the ground. Next to it on the now broken roof was a huge millstone. We didn't try to figure out what it was all about. Fredek went immediately to inform Bojarski of the accident. In a minute he was back. "Bojarski's getting dressed and will be right out." And, grinning, he added, "You know, when he saw me coming towards him, for a second he stared at me like I was a ghost. Then he clasped his head and yelled, "How did you get out?" We laughed. It still hadn't occurred to us that he had actually tried to bury us alive and that the two-wheel carriage with the millstone was expertly prepared to seal off the entrance and make any escape impossible. It had been the sudden force from the edge of the fallen millstone that had broken the main support of the roof, forming a slide, which made shifting the weight possible. This saved us from death. There was no way we could have been able to move it off had the roof been straight. We watched Bojarski's huge figure advance towards us in the murky night. "Well, boys" he said, "you'll have to return to the old hiding place. We'll think of something else later." The fatal day on the night of April 23, 1944 we were lying quietly, hungry and resigned, when we heard faint footsteps about the barn. We recognized Bojarski's tread perhaps he was bringing us food. We heard him stop before the board barring the entrance. Fredek stretched out on his belly and edged towards the opening in the straw. We heard the hatch open and the board move. A moment of silence, then a flash and the thunder of a shot. I heard Kostman scream, the rest was a gurgle and then a mutter. The board was hurled back and now we heard only Fred's hoarse deathly gasp. Szmul and I were sitting against the wall. In his final convulsions Kostman threw himself about, spraying us with his blood. After the initial shock and confusion, we realized that he was dead and it was our turn. Still we felt it was a nightmare, a kind of bad dream, but Fred's body was only too real. To reach us through the regular opening one had to crawl flat on his stomach, but now we could be too dangerous for the murderers. So they decided to disassemble the hiding place. We heard the straw covering the shelter being pushed away. We knew this was our last moment. Cramped and without weapons, we felt like rats in a trap. Szmul crawled to the other corner where he burrowed into some thick straw. I followed him. We waited. The last straw was removed uncovering the big table--our hiding place. Then the thin layer of straw covering me was removed. "I got him", shouted a young fellow happily. I begged him not to shoot and to spare my life. Holding a lantern, he looked straight into my eyes. I saw his face and the muzzle of his rusty pistol. "Where is the first one?", he asked me. I replied, "He's dead." "And where is the second?" "Next to me." I heard the report of the pistol and felt a sharp, burning bite of the bullet under my jaw. My ears rang. Instinctively and fully conscious, I took a deep breath, closed my eyes and slid down. Seconds passed. I felt no pain. I wasn't sure whether I was alive or if this was life after death. I opened one eye slightly. In the dim light, I saw the man who had shot me. He was talking in a low voice with someone. Now I knew I was alive. At the same time I wondered if I should ask him to shoot me again? If he left me, I would only suffer and die later. Or he would bury me alive. But I did not move... I felt a noose around my feet. They pulled me outside. Evidently, I was in the way of their reaching Szmul. I was put down in the mud. The night was cold. I was nude and it was raining. I opened my eyes and watched in the dark, silhouettes of the men in front of our hiding place. I heard steps and lay down again. A man approached, stopped and said, "Might be better to give him another bullet." I froze, recognizing Bojarski's voice. Someone put his hand over my mouth, I held my breath. At the second, when I though my lungs would burst, he removed his palm. He then felt my fingers in the dark probably looking for rings and said to Bojarski, "Lets not waste a bullet; he is already stiff." Suddenly I heard a scream from Szmul, "Don't shoot! Don't shoot! I want to live!" There was a shot, then another. Again a scream from Szmul, a last muffled shot, then complete silence... They returned to and pulled me inside the barn. After more poking and shaking of the hay they left, while one said to the other, "We'll bury them tomorrow; they won't rot until then and we can search more thoroughly in the daylight." When they left I crawled out, and ran to the woods. Ironically, after surviving the hell of Sobibor, Leon Feldhendler was killed in his home in Lublin, soon after the liberation by anti-Semitic Polish countrymen. Sasha Pechersky spent years in a Soviet prison. They did not believe his story and he was accused of cooperation with the Nazis. He was released when people from abroad were asking about him and his story was verified.

SOME OF THE SURVIVORS

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

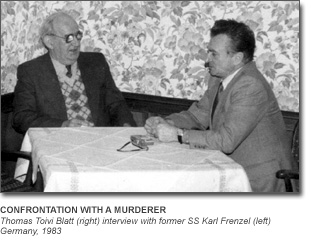

Karl Frenzel, one of the leading Nazis in Sobibor, was sentenced to life in prison. After serving sixteen and a half years, he was released on appeal due to a technicality. In July, l984 the court in Hagen rejected a defense motion to stop the trial on the grounds that Frenzel was suffering from heart problems. After a stringent medical examination it was ruled that he was fit to be retried. In l984, I was granted a three hour face-to-face taped interview with the former SS Frenzel, the man who forty years earlier had selected him to live and work at Sobibor and sent his whole family to the gas chambers. The following are selections from the author's article.

THE CONFRONTATION WITH A MURDERER "Do you remember me?" "Not exactly", he answered. "You were a little boy..." An innocent enough reply... For one crazy moment I could almost imagine this was not what it really was. We could have been uncle and nephew meeting after so many years, or perhaps father and son. Yes, there were even similarities in us. Except for his receding hairline, double chin and fuller middle, (he was seventy-three and I was fifty-six) there was the same coloring, ruddy complexion, very fair skin, blue eyes, hair once reddish, now graying, and the ample nose, quite remarkably similar in shape. It was quite possible that he did not remember me. What was I to him? But I remember him. I will never forget. I can't forget. Every night my nightmares remind me. "You are sitting here and drinking your beer. You have a smile on your face. You might be anyone in the neighborhood. But you are not like anyone. You are Karl Frenzel, the SS Oberscharfuehrer. You were the third in command in the death camp Sobibor. You were the Commandant of Lager I. Maybe you don't remember me, but I remember you." I was trembling as I faced him. "It was a dilemma", I said to him, " but I decided to come. This was the first case, as far as I know, from the World War II literature where the accused talks face-to-face with the victim and I feel it is important." I told him I put aside the moral implications and my feelings and approached him objectively simply as a researcher. I knew why I wanted to talk to him. As a man who has dedicated his life to the remembrance of Sobibor and as a serious researcher of Sobibor, I felt there were still some unanswered questions and gaps. As a former senior staff member of a death camp, one of the few still living, he could give me some technical and other important information and facts about the camp and the revolt known only by the SS. I could get the German view of events and solve some puzzling aspects of the camp. But why did he want to talk to me? I asked him outright why he agreed to speak to me. He said he wanted to apologize to me in person. He couldn't do it in the courtroom. "I don't blame you or other witnesses," he said. "And I must honestly say I was sorry for you and all those witnesses... After all those years to have to think back on all those memories and be pressured... they were pressuring and squeezing you in the court...".

This was putting it mildly. The method of the defense was primarily to discredit the testimony of the witnesses by asking them idiotic questions. In my case for example, "How tall was the tree near the barrack?" or " Was the club with which Frenzel beat your father round or not? How many centimeters?" A stranger in the courtroom would immediately have thought I was the defendant and not the victim. Now, speaking to him at the same table, privately in a hotel lobby, I was again in moral conflict. In a way, my being there with him could be interpreted as desecrating and insulting the memories of the deceased, making this murderer again a "person", in some manner, even forgiving him. I knew that many of my fellow survivors will point an accusing finger at me. Yet I wanted to talk to him. I knew if I went, I would be sorry and if I didn't, I would be even more sorry. Time will move on. I will be gone, Frenzel will be gone, but what will be written down will go to history. So, I blocked out the feelings. "I was fifteen years old. I survived because you picked me as a shoe-shine boy. But my father, my mother and my brother and the other 200 Jews from Izbica that you led to the gas chamber, did not." "This was terrible, very terrible. I can only tell you with tears, he went on quietly, calmly in an even tone, "it isn't only now that it upsets me so terribly. It upset me then... You don't know what went on in us, and you don't understand the circumstances we found ourselves in." I heard him, but nothing registered emotionally. Functioning on an intellectual level only, my mind simply sought out data and compared what he said with facts. And the facts were: SS Frenzel acted above and beyond "duty". A conscientious and efficient official, he led the incoming transports of Jews to the gas chambers. To the slave-workers, he doled out vicious beatings for slowness and other infractions. Those who became sick, or were caught committing "crimes" such as theft of food, he personally led to the execution site. Was he asking me to understand and feel sorry for his sufferings? I felt no pity, no anger, nothing. In order to interview him I turned off all feelings, just as over forty years ago in Sobibor I did not feel for my gassed parents and brother; if I had, I would have broken down and been killed. I was the objective reporter now and I wanted to know what he felt in those years. I said, "Frenzel, I would like to know what you felt then...Were you an anti-Semite or did you do what you did because you were ordered to? What I want to know is, did you believe, when you were there, that what you were doing was right?" There was a pause. I didn't realize the spot I put him in. If he said no, he would be portraying himself as a morally deficient Nazi. If he said yes, he would be portraying himself as a morally deficient human being. "No", he said quietly and evenly, "but we had our duty to do. For us it was also a very bad time." I made no comment on this comparison, but asked why he joined the Nazi Party. He looked at me dumbfounded, as if it were a silly question, and he replied, "Because there was unemployment!". As if this were self-explanatory. He told me that by chance his first girlfriend was Jewish. They were together for two years, but parted when her father, who was an editor of the Social-Democratic newspaper Vorwarts, found out that he was a member of the Nazi party. In l934, she emigrated to America with her family. "You were a member of the Nazi Party since 1930", I said. "Why are you now having a change of heart?" "No, I'm not just now," he answered, " I've cursed the Nazis and all their leaders since 1945 for what they have done. Since 1945 I have not been interested any more in politics." I noted that his change occurred when the Germans lost the war, but I said nothing. After the war he lived peacefully like any respectable citizen. After his wife's death he took care of his five children. In l962, he was arrested at his job in Frankfurt where he worked as a stage lighting technician. On his break police officers interrupted his beer drinking and asked him if his name was Frenzel and was he ever in Sobibor? He admitted he was. We went on. "Frenzel, how many Jews were gassed at Sobibor? They say over half a million. Is that accurate?" He replied, "No. I think no more than l60,000, but the railroad documents show 250,000 and many were brought by trucks, carriages and by foot." I said, "Are you a religious person?" I asked, "Do you attend church?" He responded, "Yes, very often." I then asked, "Did you have any conflict regarding your religious beliefs and political activity?" "No. We were German Christians, [A Nazi-supported section of the Evangelical Church]. All my children were christened, like myself. My brother studied theology. My wife and myself, not every Sunday because of the children, but every second or third, we always attended church." "And you have not, as a Christian, any problems with your past? " He answered immediately "I have nothing to hide. I'm sorry that I was in this mess then." "But in Sobibor you did not think about being sorry," I pressed. He answered, "We didn't know where we were till we arrived. They told us we were going to guard a concentration camp. So I had my duty to do." "Was the extermination of 250,000 Jews your duty?" He looked straight at me, "I was in jail for over sixteen years and had ample time to think about right and wrong and I came to the conclusion that what happened to the Jews in those times was wrong. All those years, I was dreaming about it...". I was listening as if from far away. I asked about his family, I knew that he had two brothers. One was studying for the pastorate. How much did they know? "Both of them were killed in the war, but my sister survived," he answered. I asked, "How about your children now. Do they know? And what are they saying?" He replied, "Naturally they wondered about Sobibor. They know it was a crime. They say, 'Father, you were also a part of it' and I explained. But they are with me and don't reject me. They wanted to know everything that happened at Sobibor. I was ordered there. I was not an SS. There were only five SS. The rest were civilians in SS uniforms." I asked why he didn't ask for a transfer if he wasn't an ardent Nazi. He wanted to, he said. He had begged his brother to try to get him out. "But the fact is," I said, "there was a case where an SS man simply asked for a transfer and was given it. He wasn't killed." Frenzel didn't answer. A hotel employee entered the room. He refilled his empty beer glass and left. We had our quiet corner again. I had many questions to ask Frenzel. As a survivor I had often wondered what a Nazi thought of the film "Holocaust". Had he seen it? He shook his head. Did he think any film or documentary could show it the way it was? "No," he said, "the reality was much worse ...it was so terrible that it can not be described." Suddenly, though I tried to block it out, a scene flashed across my mind: my friend, Leon, being beaten to death, slowly and the horror of being forced to watch his agony. Another scene flashed... Standing, listening to the muffled screams from the gas chambers...and knowing that men, women and children were dying in horrible pain, naked, as I worked sorting their clothing. I tried to keep an interviewer's tone, but my voice trembled. "Frenzel," I said, "tens of thousands of children were killed at Sobibor and you had children at the time. I've seen pictures of them. When you saw little children, five years, one year, one week old put to death. Did it occur to you, you had children also?" I didn't mean it the way he took it. Defensively, and with just a trace of anger, he said he never killed children, but was accused of it by other witnesses. His voice, until now in a low, even tone with patience and self-control, suddenly took on emotion. "I want you to know," he said and I could feel the resentment in his voice, "there was this little ten year old girl and her mother, and Wagner wanted to take them to the gas chambers and I arranged so they didn't go." There was a pause and his voice trembled slightly. "That's why it's upsetting that I'm accused of killing children." Apparently he didn't consider ordering their deaths as "killing". Someone else did the actual shooting or gassing. As if sensing my feelings, he continued, "I condemn all that happened to the Jews...I can understand that you can never forget, but I can't either. I've dreamed about it all of the sixteen years I spent in prison. Just as you dream about it, I dream about it too." Surely he wasn't comparing his nightmares to mine...or was he saying his conscience was bothering him? Frenzel was sent to Sobibor from Hadamar, a sanitarium where mentally ill Germans were gassed in the course of the euthanasia program. I mentioned Hadamar and asked how he felt killing Germans. His voice became angry. The tape ran out and so as not to jeopardize the interview, I did not insist on an answer. I decided to ask less personal questions. Did he remember "Berliner"(Berliner was an Oberkapo, killed by the Jews for cruelty to his fellow prisoners). I asked if it was true that he gave permission to the Jews to kill him. He leaned back in his chair, like an executive, "Yes," he answered confidently, "when I think back hard, it was so. My Kapo from the Bahnhofkommando told me about Berliner, then I think I said 'Butcher him to death', or something similar." His tone was frighteningly casual, as if he were speaking of getting rid of rotten potatoes. In fact, he didn't do it because he was on the prisoners' side, but because he was furious that Berliner went above his head to SS Wagner. I asked him about Cukerman (given over one hundred lashes, his body was left in a pool of blood). Yes, he remembered, he was the cook. There were five to eight kilos of meat missing, so he gave him a beating. "..Later the meat turned up and Cukerman's son said 'My father did nothing, it was me who had taken the meat.' So I gave them both twenty-five lashes. I want you to know I was always fair. I never punished unless they had done something wrong." I did not comment, but I was thinking he wasn't always so lenient. Another survivor testified in court that Frenzel caught his fifteen year old friend helping himself to a can of sardines and took him to the crematorium where he was shot. I had another leading question. What had happened to the Dutch Jews? He immediately knew what I meant. Like a superior officer, he answered swiftly and to the point, "A Polish Kapo told me some Dutch Jews were organizing an escape, so I relayed it to Deputy Commandant Niemann and he ordered the seventy-two Jews to be executed." He failed to mention that he alone led them to be killed. And I could not help noting that his voice and bearing were more forceful now and there was a feeling of competence and pride about his work. "The revolt was well executed, don't you think?" I asked proudly, but if I expected confirmation or praise, there was none. Instead, he asked a question, did I know how long the revolt took? "Fifteen minutes." I said. He agreed. "But, we worked from 3:30 to 5:30," I continued, "the time during which we annihilated your comrades. You reported it, and later Captain Wurbrand arrived and executed all the Jews in the camp. Did you leave anyone alive?" Quickly and defensively he retorted that it was SS General Sporenberg who ordered the executions, not he. I had more technical questions. Many escapees unwittingly found themselves back near the camp, having run around in circles in the forest. I wanted to know how many were caught. His face lit up. A chance to show his expertise. "Yes, about forty-five and with the 150 Jews remaining in camp, about l95. Then I had the operation (searchin camp) stopped. About seventy were killed in the revolt and in the mine fields surrounding the camp." Then, as an afterthought, looking away he added in a matter-of-fact tone, " I'm happy for every Jew who survived." I didn't comment on this irony. I dropped the subject of the revolt. "You know," I said, "Every year I travel to Sobibor. You can still find today, if you just scrape the earth, burnt bones and hair that had been cut from the women before going to the gas chambers." I wasn't really expecting a response to this and I received none. I think I said it simply because each year as I bend down and pick up a piece of bone, I feel a sense of awe. I pay my respect to those who died. Their bones do not let me forget. They seem to be crying out for justice. And there has been little justice in the finding and prosecuting of Nazi criminals. At least their deaths as Jews should not be denied! (I had in mind the sign at the entrance to Sobibor). "Frenzel, you know there is a plaque as you enter the camp today and it reads: HERE THE NAZIS KILLED 250,000 RUSSIAN PRISONERS OF WAR, JEWS, POLES AND GYPSIES." Immediately his eyes lit up. Here again, he was an authority on Sobibor. Excitedly and with emphasis he retorted, "Poles were not killed there. Gypsies were not killed there. Russians were not killed there...only Jews, Russian Jews, Polish Jews, Dutch Jews, French Jews." I was surprised at his strong reaction. I wanted it verified. It was so important. "Only Jews were destroyed in Sobibor, Frenzel?" "Only Jews, only Jews", he answered. I made sure I got it on tape. I could use this verification from a leading Sobibor Nazi to show the responsible officials in Communist Poland their manipulation of the truth. We were quiet for a moment. Then in a confidential tone, as if between friends, quietly and hesitantly and I believe sincerely, he began, "Herr Blatt, you know, when I see on television and read about Israel, I ask myself how could so many (go to their deaths)...When I see in Israel, proof of their courage, I can't understand how this could happen here...I just can't grasp it." Suddenly I realized he probably didn't feel hatred for Jews, but contempt that they were weak. I didn't let him go further. My voice trembled, "I think the question you want to ask is, why did the revolt happen so late?" Not waiting for a reply, I continued, "For one thing, the Polish Jews had already been imprisoned in the ghettos for three years and were demoralized. They were weak, members of families who were separated or killed, they were broken in spirit. They were starved, they were ill, and there were the elderly, and women with children. And the Jews from other countries, like Holland, who had not come from ghettos, who knew nothing, and had been tricked. You know how it was...". He did not comment. "Besides, I said, breaking the silence, who could believe it? They simply couldn't believe that Germans could do such a thing. They believed in Humanity. You know...the fake train station, flowers, promising speeches." I paused. Still he said nothing. After a few moments of silence I asked him once more if he believed in the Nazi racist theory. "I ask that you see me also in another way than in Sobibor," he answered. "I have much on my conscience (and here his voice had a calm strength to it)...many people, not one, but 100,000 people on my conscience...and it's okay with me, you can put it in the American press." "What do you say," I asked him," when many Germans say it wasn't so, that it never happened?" He answered, "I say it's exactly true, it's not right to say it never happened." I asked further, "So why don't you go to a magazine or newspaper and say openly: 'I'm German, I was there in charge. I worked there, and it's true.'? He said that if he told them the way Jews were murdered, he would be afraid, like the Jew, Kornfeld. (Supposedly Kornfeld, a Sobibor survivor living in Brazil, had refused to testify against SS Wagner, for fear of reprisals against him). I asked what he thought of neo Nazis today. "Are they strong or weak?" "Very weak and they should be forbidden," he answered. "Well, if they are so weak, why are you afraid to speak out?" I asked. He leaned forward and as if indicating various locations on an imaginary map, he pointed with his finger on the table. "They are here, there and if I go to the press, they have their connections." We talked for another few hours. I was trying to get more information regarding the interaction between the Nazis in Sobibor and the inner structural organization of the camp which was unknown to the prisoners. I sifted through the past, verifying suspicions and rumors. Surprisingly, I was able to verify facts that were never brought up in court and were necessary for writing the story of Sobibor. I lit another cigarette and we sat back quietly for a while, facing each other. I heard voices from outside and looked out the window. I saw on the street older women and men of Frenzel's age. I wondered what they were like back then. And those young kids...what will they become? Our interview was over. So, repentant as he claims to be, he will not speak out. He is now a free man living at home (under the pretense of illness), even though his appeal was lost on September 12, l985 and he was given a life sentence once more.

I had gained some pertinent information, but was emotionally shattered. I paid a price. I felt and still feel, a sense of guilt and betrayal for doing the interview. My only consolation is the hope that my published work will give some insight, especially to the younger generation, into how and why such an evil was possible and to the depths that hatred and bigotry can lead us. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

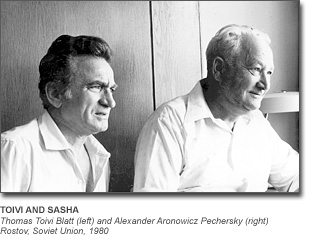

Sasha's image never left my memory. I remember him standing with me and Szlomo in front of the barbed wires, as another Jew with a ax tried to cut them. Everything was in turmoil, machine guns blasting the area, many fell. He had only a revolver in his hand which was useless against guard in the distant towers. Sasha emerged again, for a short time, as a leader when with a lager group of Jews wandered in the forest. After the war, when news reached me of his survival I promised myself to meet him someday. After emigrating to the U.S. at the first opportunity I wrote him a letter and received an invitation. This enabled me to get a visa to the Soviet Union. January 20, 1980 I boarded a plain in Los Angeles and the next day I arrived at Rostov. Sasha and his wife Olga were waiting in the main lounge of the airport. Thirty-seven years I have seen him the last time, but I recognized him immediately. In a second I was in his arms in the customary Russian "bear hug". Despite his age, his posture was straight and energetic. A taxi took us straight to the hotel. (As a foreigner I was not allowed to sleep in a private home.) In the evening he came and invited us for supper in his home. After a short walk, we stoped in front of an older, wooden apartment house. The front door led us through a narrow hall to a room at the right. This was his place. On the other site of the hall, his neighbor was a woman doctor and they shared a communal kitchen and toilet. In two small rooms, he lived with his wife Olga, a very kind woman. The furniture was sparse: a table some chairs. One corner of the room was curtained of by a bed sheet hanging on a string, forming a triangle behind which was a mirror and a shelf with a razor and other toilette necessities. Alexander Aronowicz Pechersky was born in Kremenchung in 1909, later in 1915 he moved to Rostov on the Don (river) where he studied music and theater. After receiving his diploma, he worked as a cultural director in a string of so-called culture centers where he organized amateur theaters.

At the start of the Word War II , he was conscripted to the army as a junior commander. In September the same year he was promoted on the front to lieutenant and worked in the battalion and division staffs. A month later, in the area of Wiazma, in October, 1941 he was taken prisoner by the Germans. In May, 1942 as a result of an unsuccessful escape from the POW camp in Smolensk, he was sent to a punitive camp Borysow. His Jewish heritage discovered, he was transferred on August, 1942 to a SS labor camp in Minsk. September 18, very early in the still dark morning the SS commandant Waks had a short speech assuring that the people are only being transferred to Germany to work. Three hundred grams of bread was distributed to each person and they were led to the train station. On September, 23, the train arrived at Sobibor.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||